The untold story of the barefooted Indian soccer players who helped bring down an empire

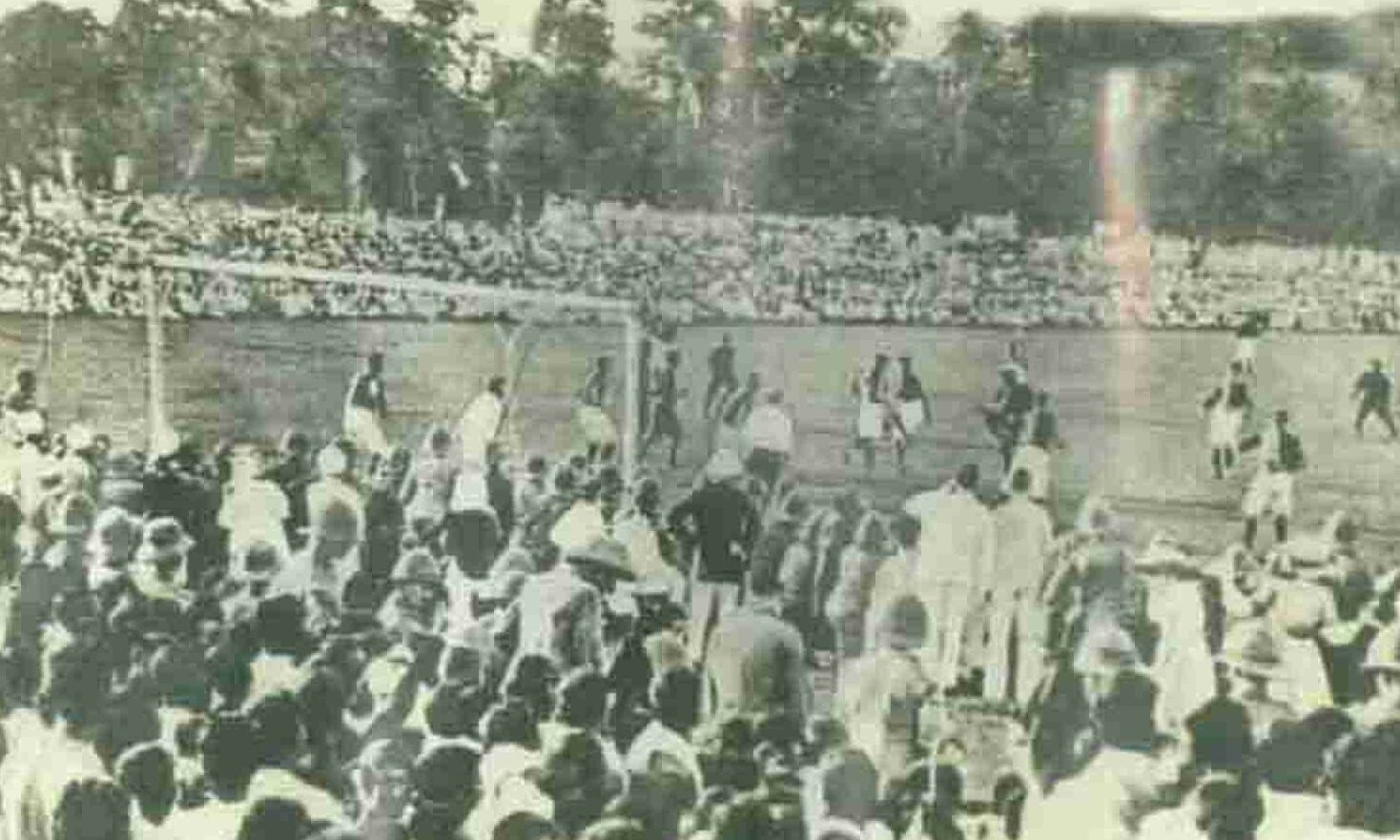

Kolkata, India, July 29, 1911. The recent monsoon rains had left the Indian capital washed clean, lush in greenery, and ready for a new start. The city was now braced for a deluge of another kind—one of football fans. Special trains and extra boats were ferrying passengers from across the region. Trams were overflowing, and horse-drawn carriages waited in gridlock traffic throughout the city. It was the final of the Indian Football Association (IFA) Shield tournament, with a team of Indian players, Mohun Bagan Athletic Club, competing against the British soldiers of the East Yorkshire Regiment.

By one estimate, a record crowd of 80,000 people flooded the Kolkata Football Club grounds that day. The facility could accommodate only 10,000, so eager Mohun Bagan fans stood atop carriage roofs, telegraph posts, and nearby rooftops. Soon even the treetops were full, with children and adults dangling from the branches. Since so few people could see the field, someone came up with the idea to set kites aloft after each goal, with the score written on them.

The seats nearest the field, shaded from the blistering sun and providing relief from the intense heat, had been reserved for British fans. English ladies in long dresses carried straw effigies of Mohun Bagan players. The Indian squad had already beaten four British teams to reach the final, an embarrassment to the British, football fans and otherwise.

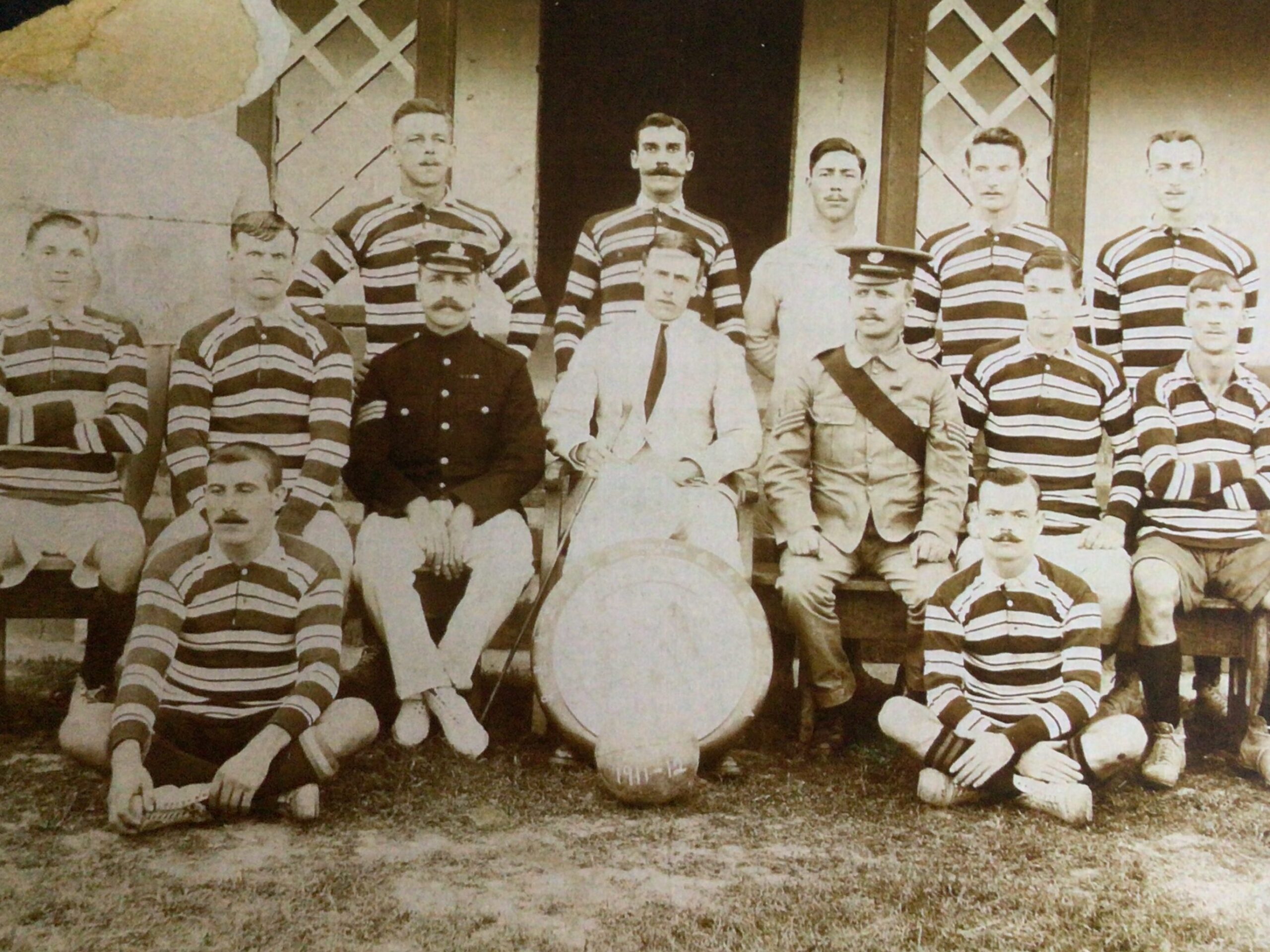

At 5:30 pm, the referee called both teams forward. British drums began pounding as the East Yorkshire Regiment marched onto the pitch. They wore black and white striped jerseys and studded boots. Led by star goalkeeper Peter Cressey, they had skillfully dispatched their side of the tournament bracket, scoring 13 goals in five matches to reach the final.

Three minutes later, the crowd erupted in cheers as Mohun Bagan took the field, led by captain and left wing Shibdas Bhaduri. According to one popular account, the players were daubed with ceremonial red marks on their foreheads and they carried blessed flower petals in their pockets, both received during their team visit to the temple of the goddess Kali that morning. The Mohun Bagan players wore bright green and maroon button-up jerseys and all were barefoot except left defender Sudhir Chatterjee. Though they were at high risk of injury, playing in their bare feet against British soldiers in studded boots, they had no substitutes.

The players knew as well as anyone that the match was a watershed moment in India’s struggle for independence from British colonial rule. “Mohun Bagan is not a football team,” author Achintya Kumar Sengupta wrote at the time. “It is a tortured country, rolling in the dust, which has just started to raise its head.”

East Yorkshire Regiment won the coin toss and elected to choose a side, which meant Mohun Bagan would kick off. The team’s 19-year old center forward, Abhilash Ghosh, placed the ball at the center spot. He and his teammates had hoped for clear skies, because it’s difficult to play barefoot in the mud. Today, the ground was hard and dry. Looming above the field was Fort William, the city’s primary British garrison and the symbol of the empire’s brute force repression. English soldiers could look down from their ramparts on the enormous Indian crowd–one large enough to start a revolt.

A Restless City

In 1911, Kolkata was still the capital of British India. Situated in the verdant region of Bengal, it was vital to the Crown for its exports of rice, tea, indigo, cotton, jute, silk, and opium. Lying on both banks of the Hooghly, an arm of the Ganges River, the city had been segregated by early British colonialists into two distinct sections: the affluent “White Town” in the south, home to British officials and merchants, and the impoverished “Black Town” in the north, dominated by Indians. But by the early 1900s, the reality was more nuanced. Despite the classic colonial division, the Bengal Renaissance had given rise to a thriving Indian elite, who invested in White Town and owned opulent compounds in Black Town, blurring traditional divisions and challenging stereotypes of Indian poverty.

Kolkata was also the British Empire’s most troublesome outpost in India, rife with newspapers rumbling with sedition and nationalism. It was the birthplace of the Swadeshi Movement, which promoted widespread boycotts of British goods, and was a base of operations for freedom fighters, who carried out bombings and political assassinations.

British officials had imposed heavy taxes on the Indian population, contributing to widespread poverty and famine on the subcontinent, while repressive laws and violent crackdowns stifled dissent. Indians were relegated to second-class status, referred to disparagingly as “coolies” and “wogs,” and encouraged to attend British-run schools, learn English, adopt “God Save the King” as their national anthem, and take up Anglicizing activities like football.

The game had been exported to India to keep Englishmen from succumbing to idleness and lassitude, which the colonizers considered the natural state of the Indian people. “By his legs you shall know a Bengali,” declared English journalist G. W. Steevens in 1899. They were skinny and weak, he reported, “the leg of a slave.” Football matches at first were confined to the European community, particularly to the British military personnel stationed on the subcontinent.

That all changed in 1877. An eight-year-old Indian boy named Prasad Sarbadhikari was riding a horse-drawn carriage with his mother through Kolkata, on their way to take a morning dip in the holy Ganges River. As the story goes, when they passed the grounds of the Kolkata Football Club, a stray football bounced toward the carriage. “Kick it to me, boy!” a British soldier shouted. The boy hopped down and kicked the ball back. According to historian Novy Kapadia, this moment marked the first time an Indian kicked a football.

Sarbadhikari would earn a reputation as “the father of Indian football.” Not long after his first kick, he and his friends pooled their money to buy a football (accidentally purchasing a rugby ball at first), learned the rules of the game from a British college professor, and established the Boys’ Club of Kolkata, the first football club for Indians.

Clubs for other sports popped up too, including cricket, swordplay, boxing, and wrestling. (Polo had gone the other direction, having originated in India and later exported to England.) Over time, Kolkata’s athletic clubs would become breeding grounds for young revolutionaries. The most notorious was Anushilan Samiti, a militant group disguised as a fitness club, which perpetrated 11 assassinations on British officials and their Indian enablers in 1907 alone.

The Green & Maroon

Mohun Bagan held its first meeting on the evening of August 15, 1889 in north Kolkata, at a white marble estate belonging to a prominent jute trader. The team would draw its name from the estate, the Mohun Villa, and its lush garden—or bagan—that served as the club’s first practice ground. The meeting attracted Bengali society’s leading lights, including one of the region’s greatest football patrons, Mahārāja Nripendra Narayan of the princely state of Cooch Behar. Frustrated that Indian teams couldn’t compete in British tournaments, Mahārāja Narayan eventually took matters into his own hands. His Cooch Behar Cup, open both to Indian and British teams, kicked off in 1893.That first year, Mohun Bagan lost to the British team Sussex Regiment.

In its early years, Mohun Bagan was bedeviled by a losing streak. The team’s fortunes changed in 1900 when Sailen Bose was appointed club secretary. A broad-shouldered, dignified man with spectacles, neatly combed hair, and an upward-curled mustache, Bose had served as an officer in the British Army. He’d learned that Brits and Indians are no different: they fought the same, bled the same, and died the same. His Mohun Bagan players had been conditioned since birth to feel inferior to the British. Bose resolved to undo that mindset.

His first step was modeling the club’s training program after that of his military regimen, emphasizing discipline, physicality, and conditioning. In one drill, as recounted in the Barefoot Boys podcast, Bose ordered his players to run up a steep slope that he had hosed down with water. Their bare feet sank deep into the mud as they climbed, which as Bose knew would prepare them for playing in rainy and slippery conditions. Another day he invited some of his army pals to the field, wearing the same type of football boots worn by the British. The old soldiers kicked and stomped on the feet of the barefooted Mohun Bagan players.

Bose also shook up recruitment. Eschewing Mohun Bagan’s typical roster of university players, he wanted raw talent: gritty, hungry, and hard-working youth. Finding them fell to India’s first football scout, Sir Dukhiram Majumder, or “Sir” for short. A former center halfback who’d played for the father of Indian football Prasad Sarbadhikari, Dukhiram was known for traveling to remote villages on his bicycle in search of undiscovered talent.

Dukhiram gave cash-strapped players money out of his own pocket, and even once biked 15 kilometers a day to deliver drinking water to a player with tuberculosis. When another boy’s father wouldn’t allow him to attend a tryout, Dukhiram gave the boy an excuse that remains popular to this day: just say you’re going to a wedding. Sir Dukhiram also dabbled in training young players, including a talented pair of brothers, Bijoydas and Shibdas Bhaduri.

The youngest of six boys, Shibdas grew up watching his older siblings play football, initially relegated to carrying their bags and clothes. His older brother Bijoydas had a beautiful game, consisting of masterful dribbling and a hint of the theatrical, faking out defenders with shoulder drops and body feints. When his teammates needed a breather, they knew to pass to Bijoydas and let him kill a few minutes dribbling.

Little Shibdas picked up tactics from his brothers and wherever else he could, including from the British. A friend visiting England brought him a book on football, which Shibdas carefully studied. After spotting some Brits dribbling between poles, Shibdas carried his family’s flowerpots to the terrace and dribbled around them. For balance training, he and Bijoydas poured water on the floor and skipped across the slippery surface.

The royal patron Mahārāja Narayan recognized the brothers’ talent and recruited them for his local team, even supporting Shibdas with a monthly stipend. He offered to buy them football boots, hand-sewn and expensive (the equivalent of a schoolteacher’s monthly salary), but the Bhaduri brothers declined the offer. They insisted they were more comfortable playing barefoot. It allowed them to handle the ball with the arches of their feet and toes, enabling tricky footwork and better agility. Plus, playing barefoot against booted Brits was regarded as a display of true manliness.

Shibdas’ capabilities exceeded even that of his older brother. “Shibdas could run like a storm,” an Indian journalist would later write. “If Shibdas was on the field, the opposition’s defense would spread a net from all sides to get him. But still, it would not be difficult for him to find the loopholes.” His skillful dribbling garnered the nicknames “The Magician,” and more vivid, “Mr. Slippery.”

The two eldest Bhaduri brothers had played for Mohun Bagan in the early 1900s, paving the way for Shibdas and Bijoydas to join the club in 1905. That year, Mohun Bagan scored a berth in the Gladstone Cup, held in the East Bengal riverside city of Chinsurah. The team reached the final and shared a train ride from Kolkata with their British opponents, the Dalhousie Club. Secretary Bose noticed Dalhousie only had seven players and asked why.

“Seven is good enough for Mohun Bagan,” a Dalhousie player quipped.

But when Mohun Bagan stepped onto the field, all eleven Dalhousie players were present. Dalhousie were the reigning champions of the IFA Shield tournament, and their imposing stature intimidated some of the Indian players. Shibdas, already the team captain, huddled his teammates. Tall and lean with an intense gaze and a quiet confidence, he pointed across the field at the white opposition. “We will attack from the beginning,” he said, an approach that deviated from their usual, more defensive, strategy.

Shibdas dominated, scoring twice within the first five minutes. The British team was stunned, watching Shibdas and his squad play with such skill, purpose, and passion. Shibdas scored four goals that day, leading Mohun Bagan to a staggering 6-1 victory, probably the most significant win by an Indian team over a British one to that point.

“If Indian football can be considered as a big tree today, then Shibdas should be considered as the root of that great tree,” Mohun Bagan’s goalkeeper Hiralal Mukherjee later said.

The Gladstone Cup marked the beginning of a hot streak for Mohun Bagan. They won a string of local tournaments, including matches against British teams. Their home field was The Maidan, a vast urban park at the heart of Kolkata. It had originally been intended as a parade ground for Fort William, which adjoined the park. The imposing star-shaped fort, armed with hundreds of cannons and surrounded by a moat, functioned as the governing base for British India and a symbol of colonial power. Now, right under the Fort’s thick walls, a threat to that power was emerging on the wide grassy Maidan in the form of eleven scrappy Indian youth in green and maroon uniforms.

Despite British teams’ vaunted sense of fair play and moral superiority, they did not always take defeat well. According to oral tradition, a British army team called the Gordon Highlanders was so humiliated after a loss to Mohun Bagan, they snatched away the trophy cup. When Mohun Bagan took the lead against their old rival Dalhousie in a 1907 match, the British players—unable to stomach the thought of losing again to the Indian squad—resorted to violence. “When our opponents were losing by 3 to 2, they lost temper, began to play very rough and even used fists and kicks upon us indiscriminately,” one Indian player recalled. Mohun Bagan fans charged the field and the game transformed into a full-on mêlée, forcing the police to intervene.

The fans’ outrage was emblematic of Kolkata’s larger turn toward nationalism. The Swadeshi movement was in full force, and passive obedience was falling out of favor. No longer would Indians hesitate to quarrel with British fans in the stands or to defend their players from thuggish opponents.

When the Bhaduri family sacrificed lambs during the Puja celebration, according to one descendant, Shibdas would spin one of the animals in the air, its blood splattering everywhere. Asked why, he replied that it represented an English-killing sacrifice.

Despite Mohun Bagan’s growing success, one trophy still eluded them, the most coveted in Indian football: the IFA Shield. Established in 1893, the tournament had never been won by an Indian team. The enormous shield-shaped trophy featured an engraving of Britannia, the helmeted female personification of Britain.

In 1909, Club Secretary Sailen Bose set out to assemble a team capable of winning the IFA Shield. Most of the players came from poor or working-class families and most held day jobs. Standouts included Hiralal Mukherjee, an agile goalkeeper despite being only 5’3″ and striker Kanu Roy, famed for his powerful long-range kicks and speed.

Mohun Bagan’s first IFA Shield appearance was a disaster, with a three-nil loss in the second round to the Gordon Highlanders. Other Indian clubs mocked Mohun Bagan’s performance, distributing insulting handbills. “As if a dwarf can touch the moon,” read one. The next year’s tournament was similarly disappointing, with Mohun Bagan losing to the Rifle Brigade in the second round. Some questioned whether Mohun Bagan should even be competing in the Shield.

The King’s Soldiers

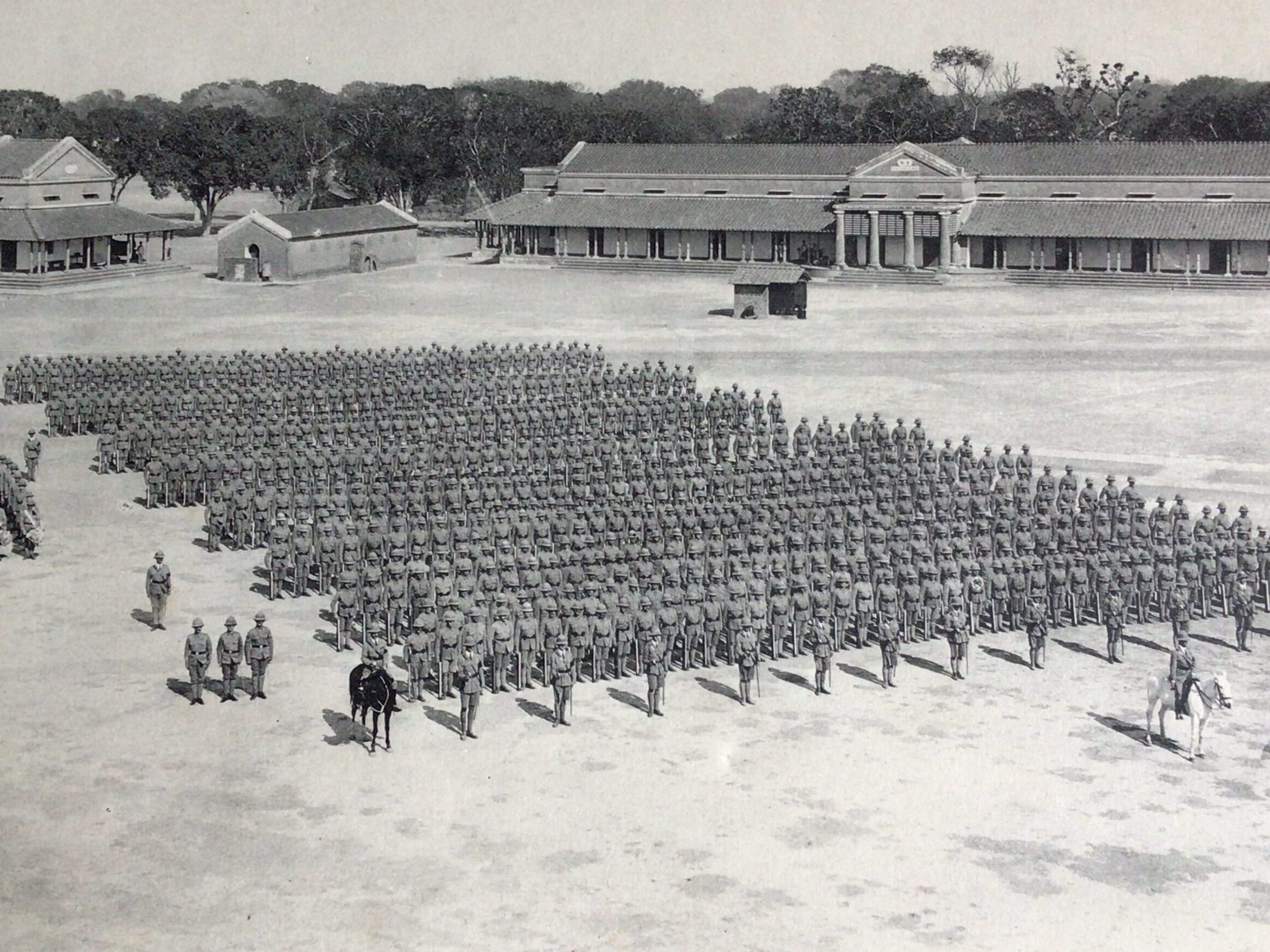

In the spring of 1911, the East Yorkshire Regiment was stationed at the Kandahar Barracks in Faizabad, in northern India. The regimental team mixed in regular scrimmages and practices alongside their official duties, preparing for two major events. The first was that winter’s Delhi Durbar, where newly coronated King George V and Queen Mary would make the first ever royal visit to the subcontinent. The second, where the British were just as keen to demonstrate supremacy, was the IFA Shield football tournament. The hilly terrain made for an uneven pitch, but the young soldiers played on.

One of the team’s standouts was the goalkeeper, Peter Cressey. The son of a shipwright from the English port town of Hull, Cressey joined the East Yorkshire Regiment at 18 to escape his menial job as a dockworker. Cressey began playing goalkeeper for the Regiment in Burma before his unit was transferred to India in early 1909. “We have no efficient substitute [for Cressey],” reported the East Yorkshire Regiment’s journal, The Snapper. “He sets too high a standard for the average mortal.”

The Snapper recorded the regiment’s various adventures in India: caring for a panther cub whom they’d adopted in Burma, shooting a crocodile in Kolkata at a range of 350 yards (“business and pleasure thereby combined”), attending the burial of a Colonel who fractured his skull in a polo accident, and gathering for a dance on an unseasonably hot evening (“dancing ladies were rather conspicuous by their absence”).

The journal also detailed certain challenges of life in the tropics for British soldiers, as in the April 1911 edition: “The hot weather which only seems to have left us a few weeks ago, is again upon us, and early hours, punkhas, mosquitos, brain fever birds and sleepless nights make us yearn for cooler climes and make us decidedly envious of our comrades at Kailana amid the breezy snow-clad Himalayas.” Diseases such as cholera were also rampant. A plague broke out in early 1911. “The deaths for Fyzabad and district average 100 daily,” reported The Snapper, including one East Yorks player who died of a swollen liver.

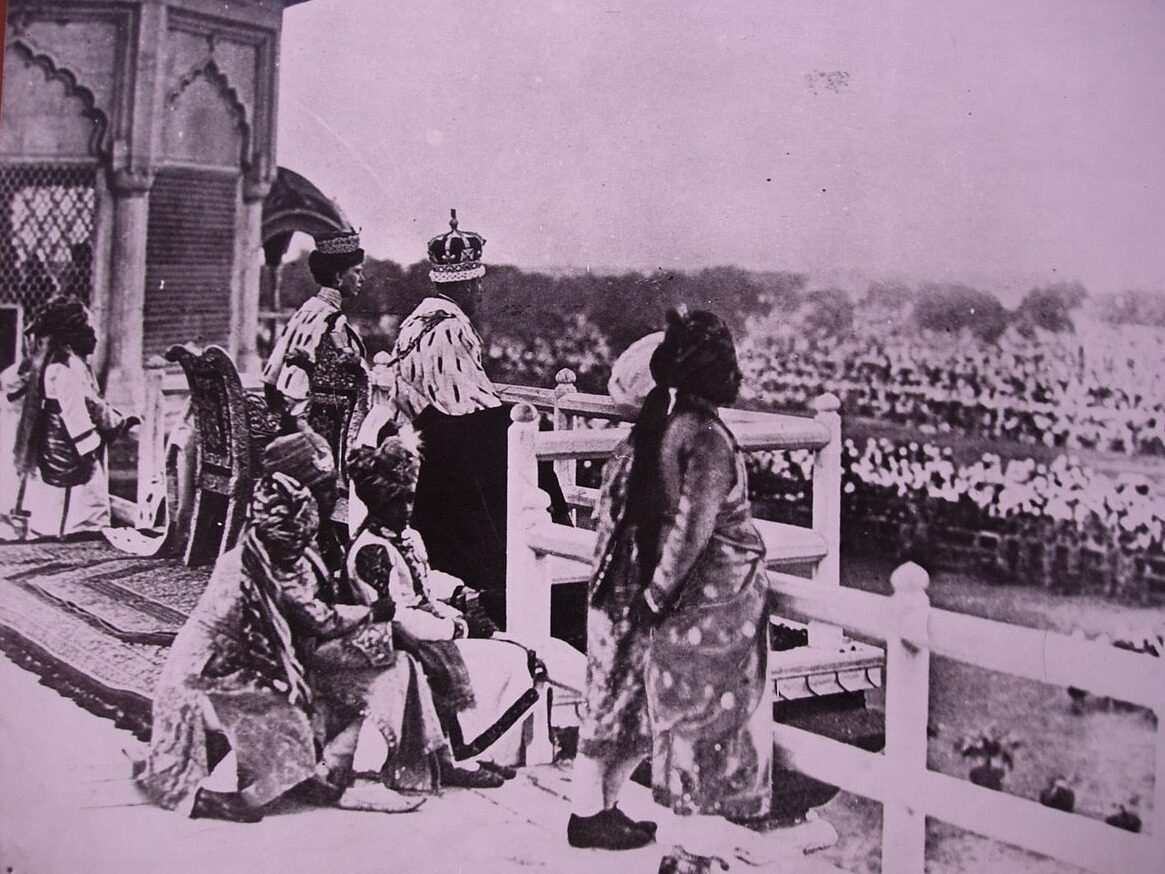

The King and Queen’s visit for the Delhi Durbar would take place four months after the IFA shield tournament. The lavish ceremony was designed to showcase Britain’s imperial dominance. Seated on his bejeweled throne in a double-platform pavilion, King George V would wear the custom made “Imperial Crown of India,” designed with 6,100 diamonds as well as sapphires, rubies, and emeralds (“It hurt my head and is pretty heavy,” the King was said to have remarked). The Durbar would feature an enormous military parade, including the East Yorkshire Regiment, and a procession of hundreds of elephants adorned in silk and jewels, some towing cannons. All the Mahārājas would be summoned to pay homage to their Emperor.

During the event, the King made the historic announcement that India’s capital would be shifted from Kolkata to Delhi. Kolkata had become too difficult to rule, with its nationalist sentiments, boycott, bombings, and assassinations.

But before Kolkata could be stripped of its prominence it had a football tournament to host. After two years of embarrassing defeats in the IFA Shield, Mohun Bagan secretary Sailen Bose knew something had to change. His rigorous training regimen wasn’t enough. So he gave captain Shibdas Bhaduri the freedom to change tactics.

Shibdas shook up the formation. He moved his youngest player to center midfield to take advantage of his unparalleled stamina. He also moved Abhilash Ghosh to center forward. Off the field, Ghosh was a smiling, soft spoken and courteous teenager. On the field was a different story. The teen was broad-shouldered, deft at using his body to shield the ball from defenders, and fearless in charging at 50-50 balls. Shibdas had long been the team’s center forward, racking up goals and winning the adulation of fans. But he saw something special in Ghosh.

The players were young, with Bijoydas Bhaduri the eldest at 30. But the squad had strong camaraderie, with some playing as teammates for five years. They’d undergone Bose’s military-style training, faced rough British teams, won hard-earned trophies in local tournaments, and shared the agony of two IFA Shield defeats. The toughest part was yet to come.

The Tournament

In its first-round match on July 10, Mohun Bagan faced off against St. Xavier’s College, made up of British students known for their physical play. Just a smattering of Indian fans turned up. The team faced a setback before the match even began: left defender Sudhir Chatterjee was missing. According to one popular story, Chatterjee’s British supervisor had refused him time off from his college teaching post in an effort to sabotage Mohun Bagan’s chances. The team took the field with just ten players.

Midway through the first half, Ghosh smashed a shot powerful enough, in local lore, to crack the goalpost as it ricocheted into the net. Bijoydas Bhaduri followed with a pair of goals to stretch the lead, and goalkeeper Hiralal Mukherjee saved an astounding three penalty kicks to secure a 3-0 victory for Mohun Bagan. The Indian Daily News praised the team’s “vigorous and incisive” forward line and called the game a “splendid exhibition of fast and tricky football.”

Four days later, despite monsoon rains that turned the pitch into a pool of mud and favored their booted European opponents, Mohun Bagan beat the Kolkata Rangers on the back of a pair of goals by Shibdas Bhaduri and an incredible penalty shot save by Mukherjee. The word was out, and for their quarterfinal match on July 19 against British team Rifle Brigade, an overflow crowd of 40,000 people appeared to cheer on the Indian team, what the The Statesman newspaper described as a “vast sea of eager exciting faces,” filled with “fire and enthusiasm.”

Despite the support, the match was mired by muddy conditions, and the first half ended in a scoreless tie. Mohun Bagan team president Bhupendra Nath Bose, an impassioned nationalist politician who would eventually become president of the Indian National Congress, roused his team with a fiery halftime speech. The squad returned to the field with force and urgency, only to see shot after shot come to naught. Finally, with just minutes left in the game, Shibdas passed to his older brother Bijoydas, who outmaneuvered two defenders and nonchalantly scored the only goal of the match. The Indian Daily News marveled at Mohun Bagan’s “magnificent defensive tactics” and overall speed, noting they were “lighter and nipper than their opponents.”

Mohun Bagan’s semifinal against 1st Middlesex Regiment would prove a sterner, and more controversial, test. Based in the Kolkata suburb of Dumdum, which housed an enormous munitions factory, the British army team was known for their rough play and for their star goalkeeper, who’d played professionally in England. Their strategy was to batter opponents with fouls and let the goalkeeper bail them out with penalty saves.

Mohun Bagan was buoyed by a roaring crowd, to that point the largest in India’s footballing history. The British players were living up to their reputations, throwing elbows and making dirty tackles, but the English referee ignored the fouls. Then just before halftime, Middlesex players went so far as to tackle Mohun Bagan’s goalkeeper while he held the ball, pushing him over the goal line. Instead of calling a foul, the referee awarded the goal to Middlesex, sparking outrage among the Indian fans. Mukherjee staggered up, badly bruised but insistent on playing on.

Mohun Bagan extracted a measure of revenge in the second half when Roy sprinted up the left sideline with the ball and launched one of his signature long-range arcing shots. The Middlesex goalkeeper misjudged its trajectory and the ball lofted over his head into the net. The crowd’s reaction, as reported by The Indian Daily News, was a “deafening tornado of cheers, which kept on a few minutes quite unabated.” The match ended 1-1. With no penalty kicks to decide the winner in those days, the two teams would need to face off again.

Thousands of Indian fans showed up for the rematch. There was a new referee–Mohun Bagan had argued that the previous one had favored the British. Rain was falling in sheets, but once again, Mohun Bagan set a wild pace from the opening whistle, pressing forward relentlessly. At one point, Ghosh collided with Middlesex’s goalkeeper and defender, injuring both badly enough that they had to leave the field. The goalkeeper, it was reported, nearly lost an eye. The Indian fans cheered the injuries in a catharsis of what one historian called “pent-up nationalism.” The halftime whistle blew with the match scoreless.

The British goalkeeper returned for the second half with a bandage over his eye, but Mohun Bagan had the momentum. The referee proved more neutral than the last. He called numerous penalties against Middlesex, provoking repeated temper tantrums from the British players. In the last ten minutes, as rain puddled on the field, Shibdas scored off a rebound, and then forwards Habul Sarkar and Roy netted goals in quick succession, notching a 3-0 win.

Mohun Bagan had secured their place in the IFA Shield final, a feat no Indian team had ever achieved. Local newspapers depicted Mohun Bagan as a brigade of freedom fighters, with The Times of India Illustrated Weekly declaring, “Every Bengalee carried his head high and the one theme of conversation in the tramcars, in offices and in those places where the Babus congregate most, was the rout of the King’s soldiers in boots and shoes by barefooted Bengali lads.”

The stage was now set for a final match, a battle not just for a football victory, but for a symbolic stand against British rule.

The Shield

There is a popular story that on the morning of the final the Mohun Bagan players visited Kolkata’s Kalighat temple. Devoted to Kali, the goddess of power and change, the temple was considered the spiritual center of the Indian independence movement.

The players waded into the muddy Hooghly River as the smell of incense wafted from the temple and morning mist rolled over the slow brown current. Then the young men entered the silent, darkened temple to meditate at the altar of Kali, the figure’s face illuminated in the rising sun.

According to the Hindu faith, a person’s fate is inscribed the moment they are born, but this predetermined path is not seen as unchangeable. Through righteous living, spiritual practices, and brave, noble actions, individuals can influence their future karma and improve their destiny. Captain Shibdas Bhaduri and his elder brother Bijoydas were keenly aware of the stakes of the day’s match. “They nurtured the possibility of achieving freedom of their motherland through this game,” Shibdas’ great granddaughter-in-law would later say. “Football was a way of life for them; it was also their flight to freedom.”

Meanwhile, goalkeeper Hiralal Mukherjee had decided not to play in the final. He was ashamed of his performance against Middlesex but also distracted by his mother’s illness. With his meager wages working at a brick kiln, he couldn’t afford her medicine. On the morning of the final, he went to the drugstore and tried to pay for the medication using a gold medal that he’d won in a previous tournament. The druggist recognized Mukherjee as a Mohun Bagan footballer and gave him the medicine free of charge. Mukherjee was reminded that what his team was attempting was bigger than himself. And that he needed to play.

Their opponents, the East Yorkshire Regiment, had received a first-round bye, but then battled through a brutal schedule that included three separate matches against the Royal Scotts due to a tie in the first game and an appealed penalty decision in the second. The East Yorks had developed a reputation as cool, highly skilled players, physical but fair.

Now came the championship game at the overflowing Kolkata Football Club grounds. As the throngs looked on from nearby buildings and treetops, the match began at a breakneck pace on the hard dry ground, with both the barefoot Indians and the English soldiers playing with an offensive mindset. Early in the game, Kanu Roy’s pass into the center was intercepted by the East York captain, Walter Jackson, but he was unable to convert. The British forwards took control, pressuring Mohun Bagan’s two defenders. The East Yorks marked Shibdas tightly and kept the ball from the Indian forwards with measured passing. The Bhaduri brothers tried again and again to pierce the East York line with brilliant individual efforts, but their advances were thwarted by offsides calls and brilliant saves by goalkeeper Cressey.

The suffocating heat weighed heavily on the players and spectators alike. Long balls from the East Yorks prompted loud clapping from the English fans, while Mohun Bagan’s counterattacks drew deafening roars from the Indian supporters. The game continued with both sides pressing fiercely, but the first half ended in a 0-0 stalemate.

Fifteen minutes into the second half, Mohun Bagan’s center midfielder and the six-foot-tall Jackson both went up to head the ball just outside the Mohun Bagan box and collided. The referee awarded Jackson a free kick. Goalkeeper Mukherjee positioned one defender in front of the ball and yelled at the rest of his teammates to clear out of the box. Jackson’s powerful free kick deflected off the Mohun Bagan defender and into the back of the net.

Black kites filled the humid sky, emblazoned with the score: 1-0 East Yorkshire. British soldiers in the crowd pounded on their drums and lifted their replica shields. The English ladies set fire to their Mohun Bagan effigies, the smoke rolling in billows above the field.

Mukherjee cursed himself for failing to make the save when Shibdas approached him. “Don’t be nervous,” the captain told his keeper. “I am repaying the goal.”

Shibdas had never been fond of Sir Dukhiram’s brand of football. It was modeled after the British style, demanding the use of boots and emphasizing physical toughness. For Shibdas, football had never been about blunt force and anger. It was about speed, agility, and vision for what could be. It was an expression of joy. If Mohun Bagan was going to win this match, it wasn’t going to be the British way; it was going to be the Indian way.

Shibdas and his older brother deployed a favorite tactic: swapping positions. It confused the British opposition, who couldn’t tell them apart. The brothers swung the ball from wing to wing with a speed and skill that impressed even the referee. “A goal seemed inevitable from this kind of attack,” he later wrote.

With ten minutes remaining, Shibdas got the ball. He dribbled past one British player, beat another, cut to the right and exploded toward the goal, firing a powerful shot at an awkward angle. The ball soared past Cressey’s outstretched hands and splashed the back of the net.

Maroon and green kites lifted above the crowd, and the Indian fans chanted “Vande Mataram!” (I praise you motherland!) Unexpectedly, Cressey left his goal and walked toward Shibdas. Nobody was sure what was happening—a brawl, perhaps? But then Cressey reached out and shook Shibdas’ hand. “Wonderful goal,” he said.

Tie game now, eight minutes to go. The East Yorks chose a defensive posture and withdrew their forwards into a wall of men around their goal. They were playing for the rematch. With three minutes left, Kanu Roy sent a long cross to Shibdas. Mr. Slippery dribbled past a pair of East Yorkshire players, drawing the defense towards him. Ghosh made a run into the open space and Shibdas delivered a perfect pass to Ghosh’s feet. With 20 seconds remaining, one on one against Cressey, he blasted the ball into the English net. Goal!

The British drums suddenly went silent. Indian fans tore off their shirts and spun them overhead. The referee checked his watch, then his shrill whistle cut through the clamor. As word of the victory spread through the enormous throng, hats, handkerchiefs, umbrellas, and arms were thrust skyward, the crowd rippling. There was screaming, hurrahs, and cries of “Mohun Bagan ki Jay!” (Hail Mohun Bagan!)

The kites showed 2-1 Mohun Bagan. Against all odds, the Indian boys had beaten the British. They had won the Shield.

Coda

The East Yorkshire Regiment players quickly exited the field. Many of them would go on to fight in World War I, where several were killed or wounded. Jackson survived the war and was awarded a military medal, while goalkeeper Cressey suffered a leg injury that ended his football career and caused him pain for the rest of his life.

The Mohun Bagan players lifted the three-foot-high Shield trophy and were paraded through Kolkata on a decorated horse-drawn carriage. The streets were draped in maroon and gold as people danced and cheered all night. A band composed of Muslim youth even briefly led the procession. The carnival atmosphere included women blowing conch shells, showering the players with flowers, and lighting lamps that flickered like thousands of orange fireflies in the Kolkata night.

While North Kolkata gleamed with light, the British neighborhoods in the south remained dark. The servants, out celebrating, had not lit their masters’ lanterns. The parade wound its way to the home of club secretary Sailen Bose, where the crowd enjoyed a public feast, a magic show, and an array of music and theater acts. Locals flocked to Bose’s house to see the Shield, touching it and kissing it as if it were a sacred relic.

Some observers, and even players from the match, credited a single individual for the win. Throughout the tournament, the younger Bhaduri brother had netted four goals and provided the assist for the score that ultimately won it all. “[I]t was captain Shibdas who won our team the Shield in 1911,” teammate Hiralal Mukherjee said in an interview.

Others saw more than a standout solo performance. “What struck was that the Mohun Bagan superiority lay in their admirable relationship, the perfect understanding with which they fought to the last,” wrote The Indian Daily News, saying the team worked like, “perfectly fitted parts of machinery.” For proving India’s strength and defying western prejudices, The Amrita Bazar Patrika newspaper dubbed the players the “Immortal XI.”

Meanwhile, British publications sought to downplay Mohun Bagan’s victory. One claimed that the scorching heat had favored Mohun Bagan, while another argued that the Indians should feel fortunate just to compete against the British. Yet another invited Mohun Bagan to England to try their luck against Britain’s best. Several pointed to Mohun Bagan’s victory as evidence that Britain’s colonizing mission in India was, in fact, working.

Local merchants in Kolkata capitalized on the victory, offering free posters of Mohun Bagan with products, issuing discounts for club members, and selling cheap footballs to encourage young athletes. Although the Mohun Bagan players were promised money, gifts, and other honors, few of these offers ever materialized. Several players, including Shibdas Bhaduri, continued playing football, but most of them returned to their day jobs, started families, and moved on with their lives.

Yet their triumph reverberated for generations. When Abhilash Ghosh fell ill in 1954, fans from near and far thronged the gates of his hospital to pray for him, donate blood, or just be in his presence. The Immortal XI had accomplished more than just a football victory. They had become symbols of anti-imperialist resistance and inspired hope for a free India. In 2009, a colored fiberglass sculpture was installed in the lane where local kids often play pickup football games. Staring down on the youngsters are those 11 heroes, with their green and maroon jerseys, stoic faces and bare feet, surrounding their Shield.

On that day in 1911, as the sun set after Mohun Bagan’s victory, the team’s flag was raised above the Kolkata Maidan. The players were walking off the field together when an elderly Brahmin priest approached the team. “You’ve conquered this today,” said the old man, nodding to the field. Then he gestured toward the Union Jack flying over Fort William. “When will you conquer that?” One of the players (some accounts say it was the defender Chatterjee while others attribute it to Shibdas), shielded his eyes and gazed at the flag. “It will come down when Mohun Bagan will win the Shield again,” he prophesied.

One revolutionary watching these events closely was a young lawyer posted in British-occupied South Africa. Mahatma Gandhi was an ardent football fan, having established The Passive Resisters Soccer Club in 1910. He recognized that football had a unifying power and could rally people to the cause of liberty. Gandhi would, of course, go on to lead India’s nonviolent struggle for independence, culminating in the country’s liberation from British rule in 1947. That was, it just so happened, the same year Mohun Bagan won its second IFA Shield.

Reporter’s Note: In the autumn of 2023, I teamed up with Barnak Das, a Kolkata-based researcher and avid Mohun Bagan fan, to track down newspaper archives, Bengali-language histories, and players’ first-hand accounts. We also learned of a wonderful podcast about Mohun Bagan called “Barefoot Boys,” and unearthed interviews with players’ descendants, many of whom still speak with pride about that 1911 Mohun Bagan squad. “They never played for money,” recalled the great granddaughter-in-law of the team’s captain, Shibdas Bhaduri. “They had devoted their lives to the cause.”

Mohun Bagan remains an active professional club and one of Asia’s oldest. “Nearly as old as Arsenal,” Das proudly reminded me, as we worked together from our respective desks 8,000 miles apart. Although we came from different worlds, we proved to be kindred spirits, sharing a passion for hidden histories, and for the beautiful game itself.

Andrew Dubbins is a Los Angeles-based journalist and author whose work has been featured in The Los Angeles Times, Alta Journal, The Atavist, and other publications.

Editors: David Wolman & Frederick Reimers

Researcher: Barnak Das

Art Director: Daniel Lehrke